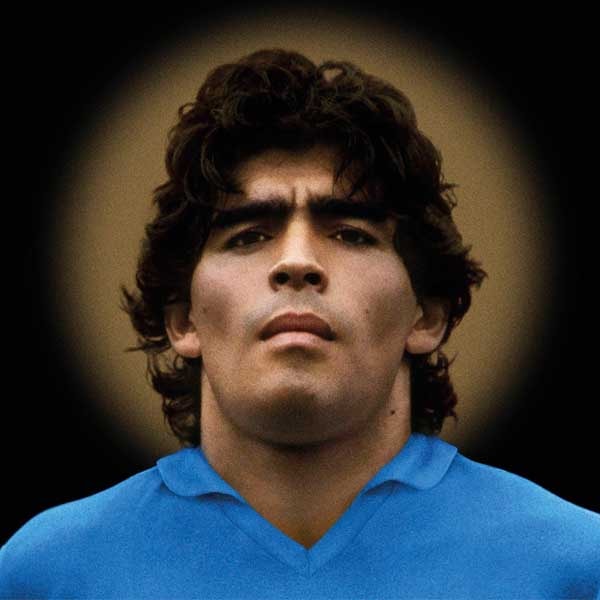

Asif Kapadia is fast carving a reputation as one of the great English filmmakers of his generation, turning the lens onto inspirational characters and tragic tales, peeling back the layers to reveal a different perspective on stories and characters that the public think they know. With critical success on his previous films ‘Senna’ and ‘Amy’, the Academy Award-winning director has now turned his attention on to the enigma that is Diego Maradona.

With unparalleled access to previously unseen footage from Maradona’s personal archive along with dedicated time with the man himself, Asif Kapadia and his team have been able to provide a stunning glimpse behind the curtain at one of football’s most controversial characters. We were fortunate enough to get a bit of time with Asif, and we discussed everything about the film, from where you start on a project such as this, to what it was like being sat face to face with Maradona.

The film is really powerful. Did you have a vision in your mind before you started to collate all the footage and catch up on all the stuff from the archives?

I’ve been doing this for a while now on different projects, so there’s a bit of a system and I guess it’s that there is no plan! If there’s one thing that I do it’s that I don’t go in there with an idea of what the film is – I trust myself and I trust the process and my team but also I know that there is a lot of story with Diego Maradona. I know there’s a lot of drama, on the pitch and off the pitch, so really what I didn’t know was where the focus would be.

We knew that Naples was going to play a big part, but my instincts were always that we were going to deal with Barcelona, I want to know where he grew up. But the challenge was always going to be where does the story end? And that all comes from talking to people and looking at the material and doing research – a lot of research goes into it.

As we go along it’s almost a process of elimination. You say, “This has to be in the film, but I’m going to have to drop this, this, this an this.” And then you think well actually, maybe the tough decision we have to make is really just to focus on Napoli. Focus on those seven years. When he comes in there, he’s quite young still, hasn’t really proved himself, he’s got a lot of pressure on his shoulders, he still looks quite vulnerable. And during the period in Naples he becomes the best player in the world, there’s no dispute – he wins the World Cup, he takes a team that’s never won anything to win the Scudetto twice, but all of his issues and problems begin there, all of which will manifest itself for the rest of his life. But the change in the character happens when he’s in Napoli.

It’s a remarkable jigsaw. How hard emotionally was it to go through so much footage? There’s so many incredible highs and lows…

It’s an interesting word, because I wouldn’t say it’s emotional. I would say it’s mentally quite exhausting, because it’s all an instinct. It’s not like a movie, where you have a script. There’s nothing written here. My instinct’s telling me that I need to talk to this person and this person and this person and I’m thinking that by talking to them, something will come out of it and maybe if we get lucky they’d say something amazing or they connect me to another person, or they have some footage.

So it’s a really odd process, because the whole thing is kind of in your head and the plan is like – you know those bad cop movies where they have a hotel room and there’s been a crime and they’ve got lots of things stuck to the walls with tape and they’ve got lines joining up, connecting – that’s what my office looks like! That’s what the inside of my brain looks like. And really, what it is is that we’re trying to create a mosaic of someone’s life, made up of lots of bits of glass that you find all over the world, dotted on the floor, that look like a piece of crap, but when you pick it up and you put it in the picture and you step away, somehow, hopefully, you’ve got the essence of a person’s life, and that’s what it’s like. So at the time, the little pieces in themselves mean nothing, but when you join them all together you hope you’ve somehow tried to nail this guy that’s really difficult to understand. He’s a very complicated bloke. He’s done some amazing things, he’s done some awful things, and so yeah, I suppose it’s mentally exhausting.

It was Fernando who came up with the concept of 'Diego' and 'Maradona', and that idea of it being two people made more sense to me than probably anything Diego himself said."

While there’s so much unbelievable access through this footage, how hard was it to leave footage that was just incredible out because it didn’t fit the narrative? You must have so much archived content that you could make multiple Maradona films?

Yeah, I tell you what, you know the opening of the film when they drive to Naples stadium? That’s mad, OK? That’s five minutes of madness. But in the previous cut, about a year ago, that five minute section was 45 minutes long. And the bit after Naples was about half an hour long. So that was just one of the versions of the film where just him growing up, getting to Boca Juniors, going to Barcelona, all the hope, everything goes wrong, all of his issues – that’s before he got to Naples.

The problem was that the film always felt like it was going along, then starting all over again. And that’s for each bit of his life. What we realised was that there was this cycle of hope and brilliance and then death and destruction and resurrection and hope and brilliance. So what we ended up doing, my editor, Chris King and I, was we looked at everything. I’m going to do all that work so that you don't have to, I’m going to pick what I think is the best two hour version of this story, and that is Napoli.

Most young people now only know the latter Diego Maradona: he’s out of shape, he looks really obese, he doesn’t look good, he became a bit of a joke figure. And the idea of the film was to show that this guy was amazing, look what he did. How did he become that person that we saw during the World Cup last year? We’re hoping that our film somehow explains the journey he went on from being the young innocent, vulnerable looking player to the best player in the world, to the person that we saw during the World Cup last year.

How does the journey you went on making this movie compare to Amy and Senna?

It’s a good question, because I guess the biggest difference is that he’s around, he’s alive. So I could meet him and talk to him, but getting to meet him and talk to him is not simple, because, well, we’re editing in Clerkenwell in London, he’s living in Dubai, the story takes place in Naples in Italy, and most of the voices and contributors are in Buenos Aires!

Senna was a film about a Brazilian guy and I went to Brazil and I travelled a bit on that film, but most of the story and the footage existed in the UK. The main language of Senna is English. With Amy, it’s set in North London, I live in North London and I’ve lived there for most of my life, I’m a local boy, I was in Camden for ten years or so. So that was about making a film about where I’m from. This story was a challenge because of the distances, because of where everyone lived, because he’s alive, because he speaks in Spanish – Argentinian Spanish at that – and the story’s in Italian, in Naples. I don’t speak Spanish or Italian.

He is the master of deception, he is the master of dropping a few bombs, which send the conversation off on a tangent."

Also, meeting him takes a long time. Then when you do meet him, you start talking to him and you’re thinking, well what does he remember? And then you realise that sometimes he’s created his own story now in 2018/19 which isn’t necessarily the best depiction of what was going on in the mid-80s. His answers are not always relevant, because he doesn’t remember or he goes off on a tangent and I ask a question about some sort of personal thing from his life and he gives me a long answer about Sepp Blatter! It’s great, it’s fascinating, but it’s not really what I want. I’m asking you about your son, or something like that. So he is the master of deception, he is the master of dropping a few bombs, which send the conversation off on a tangent, but when I'm doing this kind of a film, I’m just going to keep coming back to the same question. You can see it winds him up, because that’s not normally how people talk to him. So it was a fascinating learning curve for me, because it was a challenge, and I think the interesting thing is, having made a few of these films, it’s only worth doing if it’s a challenge.

How did you feel as you were interviewing him, was the structure of the film coming into your head with everything he said?

I would say that meeting with Diego Maradona is an experience in itself. Obviously, being a football fan, just being in the presence, going to his house, as far as I’m concerned I’ve played football with him – in his opinion some bloke passed a ball to him and he passed it back once, but in my mind I’ve played football with Diego Maradona. I’ve sat at his feet and looked at his amazing legs and stared at his foot and gone, “That’s Diego Maradona’s left foot”. And then I’ve touched it. He didn’t want me to touch it, but I did, I couldn’t help myself!

So there’s that kind of mad experience of being in the presence of this icon, being able to ask Diego Maradona about his goals against England, being able to ask him about lifting the World Cup and where he came from and playing for Napoli – that is just an amazing experience which I didn’t have with Senna and Amy, I couldn’t talk to them. But, the other side of it is having him around doesn’t necessarily make it easier because I’ve got to go away and make the film and we’ve got to deal with the tough issues and the film is a separate entity.

What I don’t do is I don’t turn up with a camera crew to interview him, I just do audio. I don’t want a performance, I don’t want him to play to the camera or play to the crowd, I want a different kind of interview, which is interesting, because he knows when to turn it on. And he’s great when he turns it on, but it’s not really helpful for me.

As far as I’m concerned I’ve played football with him – in his opinion some bloke passed a ball to him and he passed it back once, but in my mind I’ve played football with Diego Maradona!"

Then also there’s just times when you realise the most reliable people are the people around you, and so for me Fernando Signorini is amazing. He’s a trainer who I’d never heard of before the film. He was really honest and really tough. He was there, he knows Diego, knows everything that went on, his private life, his professional life, and I thought he was an interesting guy, because I’d never heard of him, but he became one of the key characters.

It was Fernando, for example, who came up with the concept of “Diego” and “Maradona”. And that idea of it being two people made more sense to me than probably anything Diego himself said. What you realise is that everything that he’s done, everything that I’ve witnessed I can now get my head around, “Oh that’s the nice guy and that’s the other guy. The same guy, but he’s somewhere on this spectrum." And on one end of it is Diego, one end of it is Maradona, somewhere in the middle of it is Diego Armando Maradona and depending on the day of the week, you’re meeting someone on that range. It helped me and it helped when we were making the film, and when I brought that concept up to people everyone kind of went with it, because everyone could see that there were these different sides to this character.

His voice over is so giving. He opens up his darkest truths, how did you approach the need for transparency with this film?

Because of the nature of what I was doing, I knew that we’d be dealing with trickier subjects and therefore I’m only going to be able to put it in the film if I brought it up and broached it with him directly, but I kept thinking that I’d do it in the first interview. On my list of difficult questions there were some really easy ones, but when I brought up certain people he was like, “I don’t want to talk about her. Never bring her name up again.” And I was like oh god, that was an easy question! Then I brought up someone else and he said “He stole money from me, I don’t want to talk about him.” And I’m thinking how am I ever going to get this done?!

So I kept thinking that I’d have to do it on the next trip. There’s a lot of things that I have to talk about, so I dealt with those on the second trip and it was all going well, everyone was really happy, so I said, “Can I come back again tomorrow?” and he said yeah, sure. It was going well, and I thought, OK, I have to deal with all the heavy subjects. Every time he went off on a tangent I would interrupt him and bring him back. And I don’t think he was used to being interrupted when he was mid-flow, but I knew I only had about a 90 minute window and I had a lot of heavy stuff that I wanted to talk about, because I did not want him at the end of it, when he sees the film, calling me a pancake like he calls all the journalists on that plane flying back from Mexico! The worst thing ever would be if he called me a two-faced pancake! So I’m going to go through all of the heavy subject matter, and we did. He didn’t always like it, but he did answer the questions about all of them. There was a couple of points when he got a bit annoyed and he did say, “You’ve got a real nerve, asking me these questions,” And I was like Uhhh, but he said, “For that, I respect you, because most people would never have the nerve to ask me about this stuff to my face.” I was like, OK, great, can we go back to the question…

There was a point where I went over and over a few things and that’s when he did say, “Enough, I’ve given you too many hours, I was told this was only going to be an hour,” you know, that thing of playing the contract against me did come out at one point when I just kept going back over difficult questions. I was like, “Just one more.”

“NO.” And it was over. It did end fairly abruptly, I have to say, but everything in the film where you hear his voice, all those tricky subjects, that’s all from the interviews that he did with me, so as far as I’m concerned, we talked about it all. He hasn’t seen the film yet. What I did do is I showed it to all of the people around him, his family, his children, his trainer, Signorini, his biographer, people who know Diego Maradona very well. They’ve all seen it and they say the film’s tough, but it’s totally honest.

The little pieces in themselves mean nothing, but when you join them all together you hope you’ve somehow nailed this guy that’s really difficult to understand."

It’s such an incredible window into life in football in the late 80s. Everything is so pure from a cinematic sense – you see everything and nothing is over polished. Do you think in today’s world we’re losing a bit of raw beauty in the way everything is so neat and tidy?

It’s really interesting that you mention that, because I’m an old school film maker and I started off making films on film, and shooting on film and editing on film and projecting on film. And what happens on film is you add a texture. There’s imperfections in film: there’s grain, it gets dirty, it gets scratched. It’s alive and it gets damaged with age. Gradually, we’ve gone over to digital and I’m not a massive fan of digital because it’s too clean and too perfect, and it doesn’t always look great; it looks fake sometimes.

So the interesting thing that I’ve found in my own weird journey as a film maker is that I’ve been doing these archive films, and partly I’ve gone through the process of making films out of footage that is technically really crap sometimes, or imperfect, shall we say. But what I find interesting is it’s real. That’s raw footage, real footage. That’s really Ayrton Senna, and when he drives at 200 miles per hour that’s what would happen to a camera; it’s shaking all over the place and there’s glitches and I don’t take them out, I leave all the glitches in, all the imperfections. Same with Amy. Some of the earlier footage is awful quality but that’s her, at that moment, singing that song, and it’s great because it’s real.

With this, the idea of some bloke standing on the side of a pitch – you could never do this now – that guy shooting the footage, whenever you see Diego in a Naples game from the cameras behind the goal or on the side of the pitch, that’s his own personal cameraman who’s allowed on the pitch to film. So what’s interesting is that I love the shakiness of it. This is pre-steady cam; they’re not running around with super digital, it’s not perfectly sharp. It’s the imperfections of people, humans, Diego Maradona, the pitches, the kits, the weather, all of that, that’s what I love. That’s what we’re trying to show.

This is how football used to be; look at the state of the pitches, look at the state of the tackles, look at the kind of characters. That’s what we’re trying to show. It isn’t like that anymore. It’s been cleaned up, everyone’s been PR’d and he was never like that. He’s from a different age and that’s what I like. It’s the imperfections, not just technically, but in humans that I’m interested in.

'Diego Maradona' is out in cinemas on June 14.