Louis Bever sits at the intersection of football culture and fine art. In this edition of VANGUARD, he talks selfish creativity, crest controversy and why the best work starts with simply caring enough to make it.

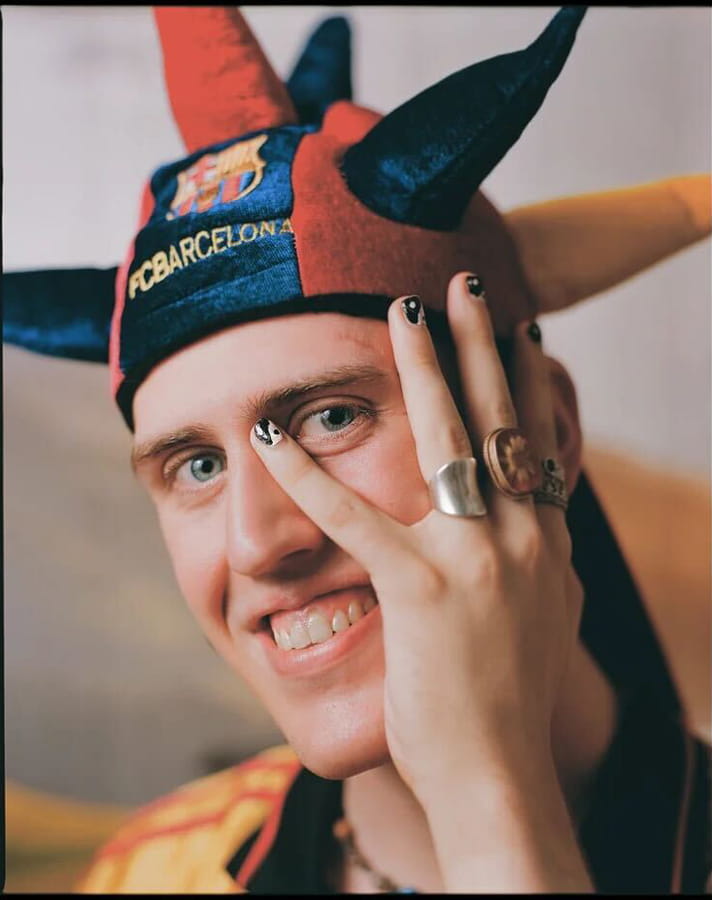

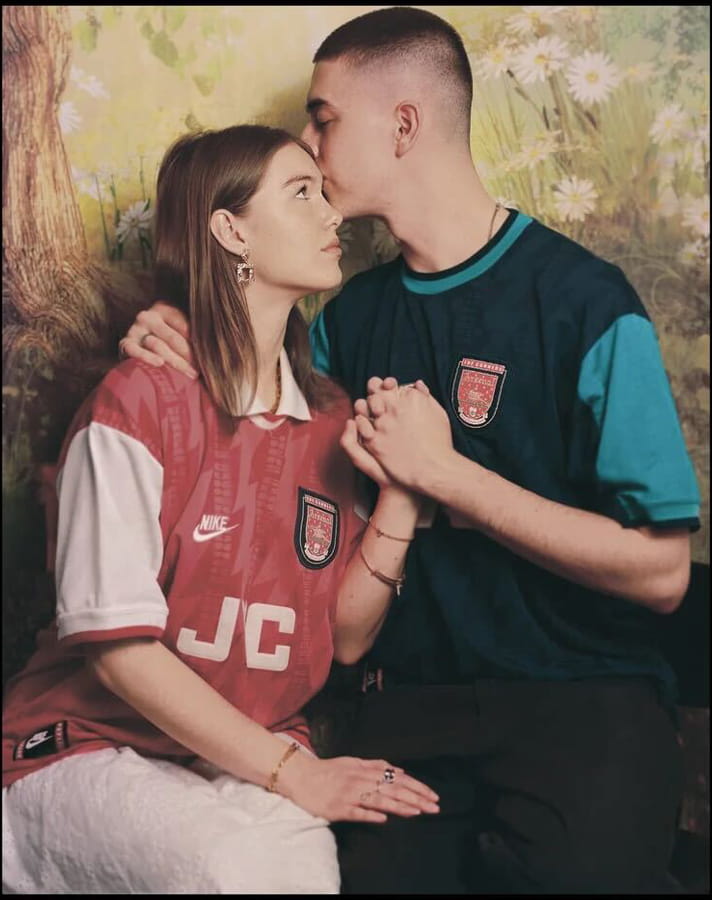

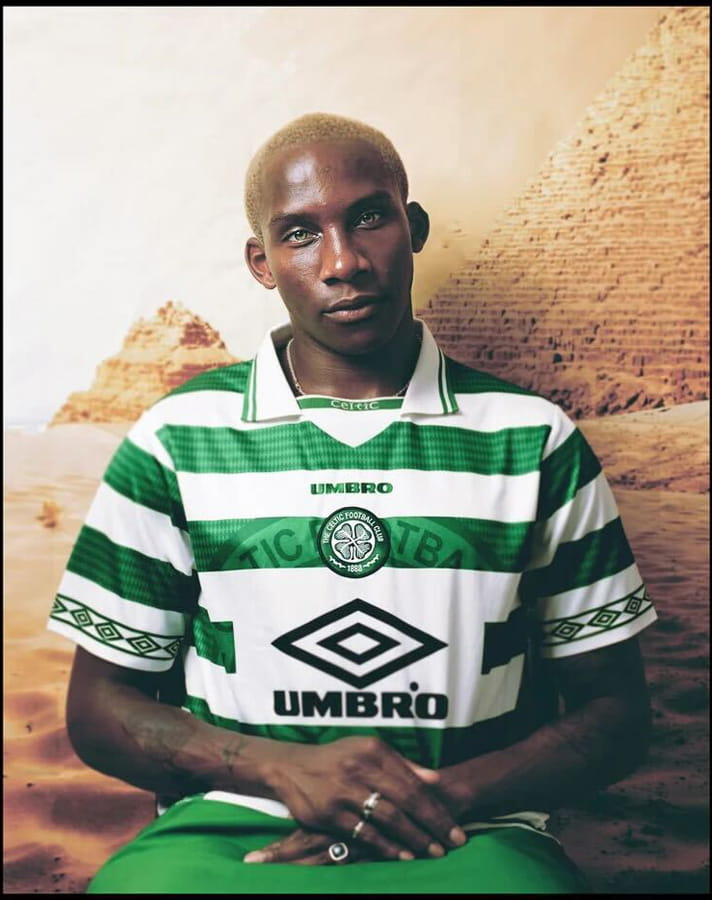

To start, Bever describes himself as “someone who documents all things football, inspired by all things art," which is a line that sounds almost throwaway, although it neatly captures the world he's carved out for himself. A photographer and creative based in London – not to mention a die-hard Arsenal fan – he's has built a body of work that sits comfortably between matchday ritual and museum wall.

Raised in a big football family and moving countries every few years, the game became a constant with Bever, a language he could rely on wherever he landed. His dad clung to live scores on Ceefax while living abroad, loyal to Stockport County and Manchester City long before the Abu Dhabi era, while his mum introduced him to art galleries and old masters.

Saturdays were for matches; Sundays were for paintings – a split that now shows up in Bever’s work. Nostalgia is the red thread through everything Bever creates. There’s humour too, and a healthy refusal to take the creative industry too seriously. For him, the sweet spot is simple: make what you like, share it, move on.

We caught up with him to talk about selfish creativity, cultural missteps, melancholic cinema and why, sometimes, the best thing you can do is just crack on.

What was your first real connection to football culture not the game itself, but the world around it?

I’m from a big football family, so it was always there. My dad had the TV on with Ceefax and live scores. He’s a big Stockport County and Man City fan, and because we were based abroad, that was his closest link to English football. I remember being five or six in Paris and watching him constantly let down by City. He’d always say, “City will win the league one day.” The most passionate fans in my family are actually my two nans. We moved every two or three years growing up, and football became a universal language. No matter the background, you could connect through it. That fascinated me.

Your work sits between football and art. What does football give you that other subjects don’t?

It’s important to photograph what you genuinely care about so it doesn’t feel like work. I collected shirts. I lived around football. At the same time, my mum dragged me around art galleries when my dad wasn’t dragging me to matches. I’ve been taking pictures since I was 10 or 11, but it wasn’t until my early twenties that I realised all my images were influenced by paintings – and nearly all of them featured football objects. Those were my favourite pictures. The combination just makes me happy. Other subjects don’t really do that for me.

What are you most obsessed with in your practice right now?

The idea that the two most important parts of photography are the initial idea and the final image. I live in a city where everyone’s obsessed with process – pushing and pulling film by a gazillion stops, developing it in Italian natural wine or whatever. I just don’t care about that. I want to hear the idea and see the finished image. I see people renting studios, photographing their equipment, talking about how many rolls they shot – and then you never see the final work. Share the bloody work and crack on. If you think you’re special, you’re not. If you think you’re replaceable, you are. It sounds harsh, but it makes your creative life easier.

Football culture has a long visual history. How do you balance respecting that with pushing forward?

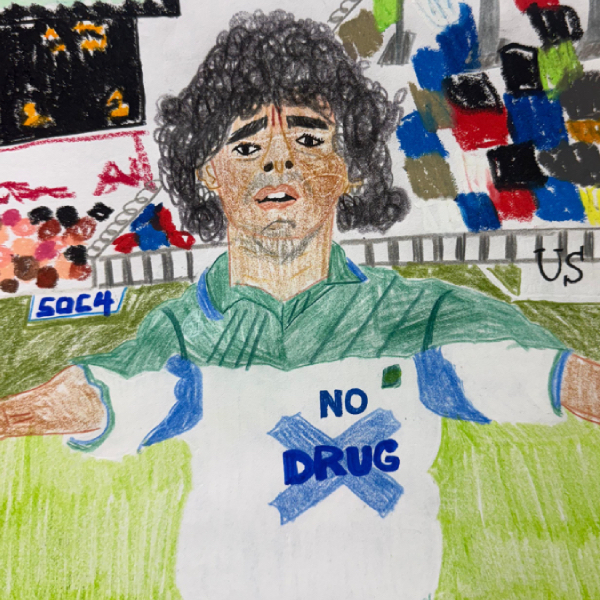

You have to do your research. In English, French and Italian football, I grew up around it, so I know the boundaries. But I once flipped a Brazilian club crest upside down in an image. I’d done it before with an English club and people loved it. With the Brazilian club, someone threatened to come to the UK and fight me. I later learned that flipping a crest 180 degrees is a huge sign of disrespect in Brazil. If you cock up, apologise, learn and move on.

Was there a turning point where things clicked?

Realising that being selfish about what you photograph benefits you long term. Someone once said every photo is a self-portrait. They’re not wrong. If I started shooting techno DJs in vintage ski gear, it wouldn’t make sense. I don’t ski and I don’t like techno. Matching artwork to football memorabilia made me happy. When commercial work started coming from that odd niche, that’s when it clicked.

What does “authentic” soccer culture mean to you in 2026?

You can tell when someone truly loves football, their eyes light up. Ten minutes turns into an hour. I’m a lifelong Arsenal fan on my mum’s side and I live in East London. I’ve seen people suddenly like football to fit in. I don’t mind, but they can be the worst to watch a game with. You weren’t there for Puma Arsenal. Blokecore didn’t help either. A lot of people like the idea of liking football. You can tell the difference.

How do you protect your point of view in an increasingly commercial space?

Commercial work is commercial work. Personal work is personal work. Don’t mix them. I don’t consider myself a commercial photographer because I’m too stubborn – I’ll always put my twist on it. The more niche your subject, the better. If you chase trends, you’ll spend your career chasing them. If that frustrates you, stop.

Who or what outside football influences you most right now?

Art and music. I’ve started making videos and realised I’m drawn to sad films and melancholic art. My favourite films are Midnight in Paris, Lost in Translation and Her. I’m a happy person – my two loves are my job – so I need a bit of sadness somewhere. It ends up in the work. Art feels like a time machine. Looking at a brushstroke from the 1600s and imagining the artist making it blows my mind.

Looking ahead, what do you want to be remembered for?

With football, I’m not sure. With photography, I’d like people to remember that it’s not hard to take a picture. You don’t need a big studio or expensive camera. You need an idea, some space and people you trust. I’ve shot commercial projects in my flat that look no different from studio work. But if Arsenal win the league and I’ve shot the campaign for that third shirt, I’ll make sure people know about it.

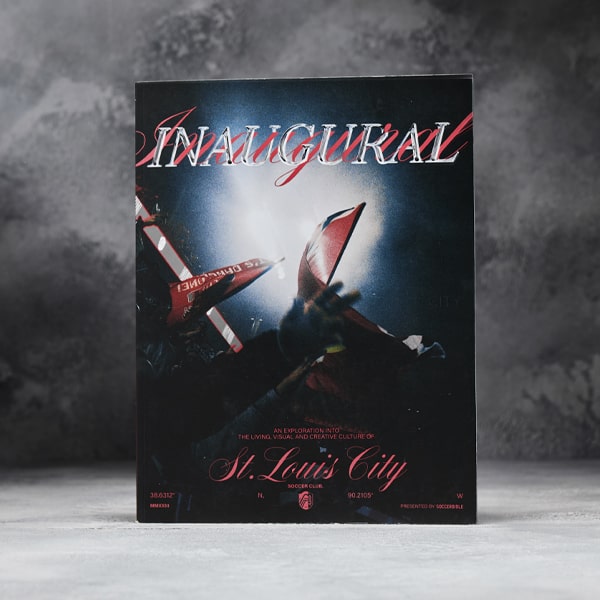

VANGUARD: The Creative Soccer Community is SoccerBible’s ongoing celebration of the people reshaping the seams of creative soccer culture – the photographers, designers, filmmakers, stylists and thinkers redefining how the game looks, feels and lives beyond the pitch. It’s a platform for individual voices and distinct perspectives, spotlighting those building new visual languages around football while respecting what came before.

You can check out more of Louis' work on his Instagram page